Shock, Moral Panic, and Newsworthiness in the Music Industry Post-Columbine

Izzy Grady

[MUS001120M-S3A-A] Capstone Project Module

MA Music, Management and Marketing

University of York

1. Introduction

Marilyn Manson, both as a solo artist and as the frontman of his eponymous band, has long occupied a uniquely polarising space in contemporary music culture. Emerging in the early 1990s with an aesthetic fusing theatricality, provocation and nihilistic lyricism, Manson became emblematic of a subgenre widely referred to as “shock rock” (Halnon, 2004, p. 747). His deliberate transgression positioned Manson as a catalyst for cultural anxieties, especially among conservative commentators and mainstream media (d’Hont, 2016). This cultural tension intersected with the broader “Satanism scare” of the late twentieth century, which heightened media scrutiny and public fear, a phenomenon which scholars have deemed a “moral panic” (Reichert & Richardson, 2012, pp. 48-50). Within this context, alleged links to Satanism, even when unsubstantiated, could stigmatise individuals as “morally unfit or even embodiments of pure evil” (Reichert & Richardson, 2012, p. 52). This spectacle-outrage dynamic later materialised as a nationwide moral panic, making Manson a case study in constructed, vilified ‘deviant celebrity’ (Parnaby & Sacco, 2003) .

The events following the 1999 Columbine High School massacre marked a profound turning point in the reception of Manson’s public persona (Waterson, 2017). Despite the absence of direct causatory evidence linking his music and performance to the perpetrators, Manson was rapidly transformed into “the antithesis of stability, order and security” (Walsh, 2017, p. 645), a convenient vessel for cultural blame in a period of American moral decline (Osborne, 2017, pp. 43-44). This cultural rupture provides a critical lens through which to explore two interrelated questions: how Manson was cast as a scapegoat within a wider moral panic, and how his subsequent response functioned as a strategic act of brand management.

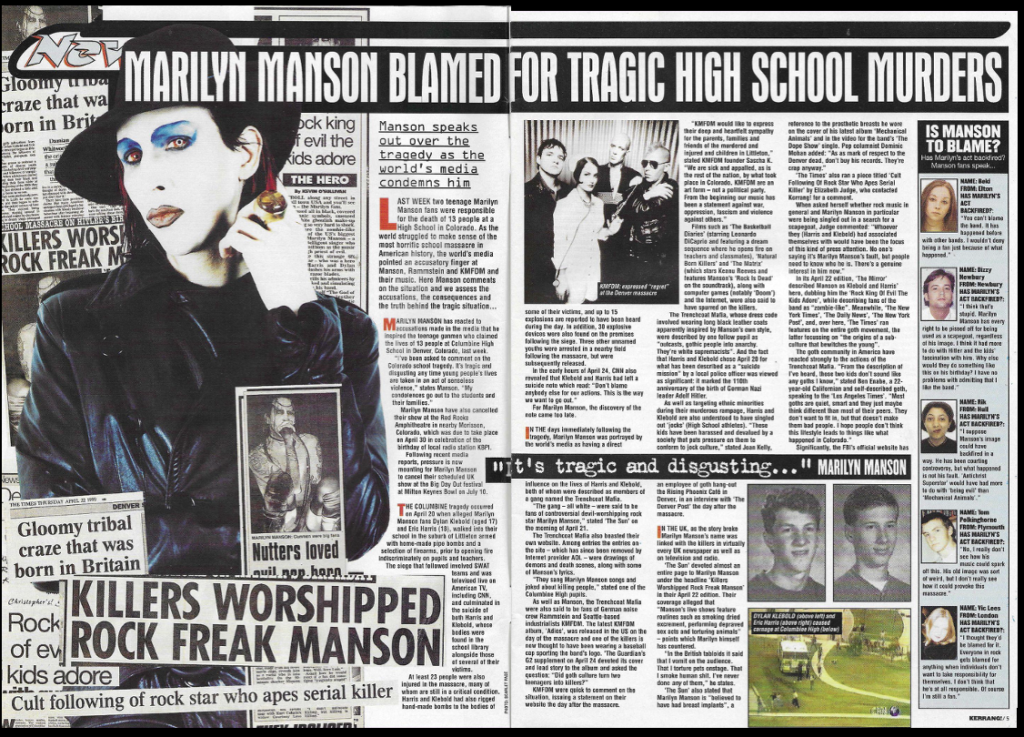

On the 20th of April 1999, two students of Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado—Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold—carried out a coordinated attack on their school, killing 12 students and 1 teacher before taking their own lives. At the time, it was the deadliest instance of school violence, sparking a wave of national mourning, political inquiry and media speculation. In the absence of a clear motive (Hong et al., 2010; Kiilakoski & Oksanen, 2011; Strauss, 2007, pp. 812-816), media outlets turned to the perpetrators’ cultural interests—including trench coats, violent video games and industrial metal music. Manson’s name, aesthetic and lyrics soon became entangled in media hysteria [See figure 1], which extended far beyond the bounds of music journalism.

Figure 1

Magazine article scan referencing Marilyn Manson. Kerrang!, May 1999, pp. 4-5

Importantly, the sheer scale of the media spectacle surrounding Columbine was not incidental—it reflects broader logics of newsworthiness. As Gekoski, Gray, and Adler argue, homicides involving statistically deviant offenders and “perfect” victims are more likely to attract media attention (2012, p. 1222). Columbine exemplified both dynamics: the attackers were white, suburban teenagers— unlikely agents of mass violence (Schildkraut et al., 2025)—and their victims were mostly students in a middle-class area. According to the Pew Research Center (1999), 68% of Americans followed the Columbine shooting ‘very closely’, and 92% followed it ‘fairly closely’ (see Table 1). Gruenewald et al. (2009) further contend that victim demographics, especially age, drive media interest in homicides (p. 268), suggesting that the cultural status of the victims contributed significantly to Columbine’s high-level coverage. In this media environment, figures like Manson become not just relevant, but narratively necessary: cultural symbols onto whom societal fears can be projected. As observed by Victor, in the aftermath of collective struggle, communities often rely on symbolic narratives that demand villains: figures who supposedly embody moral decay, even in the absence of clear evidence (1993, p. 107).

Table 1

Top News Stories Followed ‘Very Closely’ in 1999 Among U.S. Adults

| News Story | % Followed ‘Very Closely’ |

| Shooting at Columbine High School | 68 |

| Death of JFK Jr. | 54 |

| U.S. Soldiers captured near Kosovo | 47 |

| Hurricane Floyd destruction | 45 |

| NATO air strikes against Serbia | 43 |

| Tornadoes in Oklahoma and Kansas | 38 |

| Cold winter weather | 37 |

| U.S/Iraqi military clashes | 37 |

| Senate impeachment trial | 31 |

| Crash of Egypt Air flight | 30 |

Note. Adapted from Pew Research Center (1999)

The Columbine tragedy constituted a critical juncture in the media’s treatment of controversial figures, particularly those associated with non-mainstream musical genres. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Manson was subjected to an orchestrated wave of scrutiny and condemnation, emblematic of a broader tendency in crisis moments to reduce complex social phenomena to simplistic causal narratives (Frymer, 2009, p. 1402). As Birkland and Lawrence (2009) argue, tragedies like Columbine provide “focusing events” which intensify public concern and incite journalists to identify cultural malefactors p. 1412). This dissertation examines Marilyn Manson’s cultural framing as a “folk devil” (Cohen, 2011), and how he in turn, engaged with sustained media hostility, and through strategic responsive brand manoeuvring, redefined his image rather than retreating from controversy.

The central research question guiding this inquiry is:

To what extent does Marilyn Manson exemplify a cultural scapegoat during a moral panic, and how can his response post-Columbine be understood as a form of strategic brand management in the face of sustained media controversy?

Subsidiary questions include:

- How was Marilyn Manson framed by mainstream media in the immediate aftermath of the Columbine shooting, and what discursive mechanisms contributed to his positioning as a cultural scapegoat?

- What branding strategies did Manson adopt in response to public backlash, and how did they function to reclaim narrative control?

- In what ways did Manson’s media portrayal diverge from or reinforce established patterns of moral panic theory and folk devil inception?

To address these questions, this study adopts a multidisciplinary framework drawing from media studies, cultural sociology, and popular music theory—in which concepts of media framing and moral panic serve as key analytical tools. Framing theory, first introduced by Goffman (1986), and later refined by Entman (1993), examines how narratives are selectively constructed to shape audience interpretation. Cohen’s moral panic theory, first published in 1972, provides a lens through which to analyse how societies react to perceived threats by scapegoating individuals deemed “deviant or socially problematic” (2011, p. 27). Integrating these theories of newsworthiness and celebrity studies allows for a robust interrogation of Manson’s media representation and self-presentation.

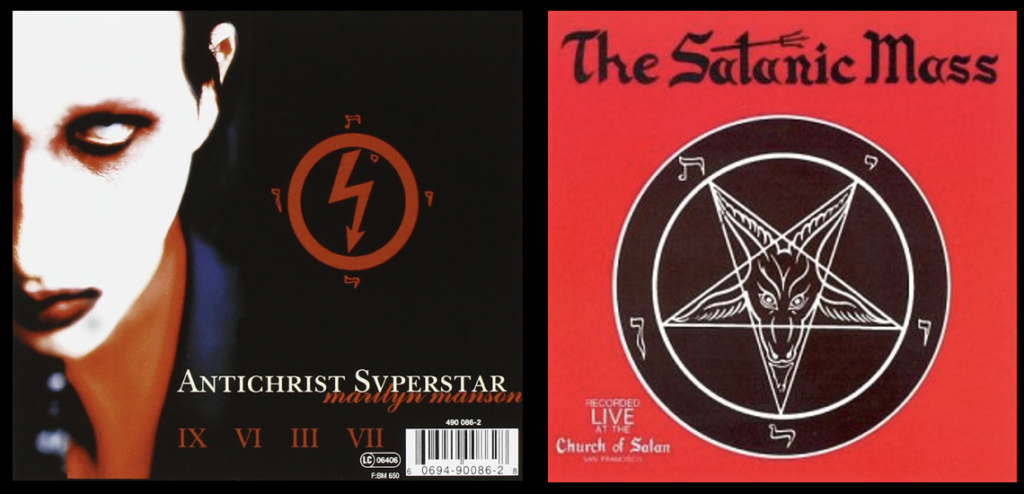

In his 1993 work dissecting the Satanic Panic, Jeffrey S. Victor notes: “Satan symbolizes the loss of faith in legitimate authority… The evil enemy image functions, just as in times of war, to confirm our society’s essential goodness.” (pp. 77-78). Within this context, Manson’s self-styled identity as the Antichrist Superstar (see Figure 2), became a powerful symbol of cultural breakdown, intensifying the moral outrage he attracted. The iconography of this album, more explicitly, its religious inversion, contributed directly to his framing as a moral threat. As Osborne notes, “Manson desires to be viewed as the Antichrist and uses “Irresponsible Hate Anthem” as a method for providing his audience with the deviant labels in which to readily interpret his ambiguous persona” (2017, p. 49). In doing so, Manson actively, albeit unknowingly, cultivated the very imagery which would later be weaponised by mainstream media in the wake of Columbine. This symbolic function is essential to understanding why he became uniquely scapegoated following the attack.

Figure 2

Front Cover Art for Marilyn Manson’s Antichrist Superstar (Brown, 1996)

While significant academic attention has been given to moral panics, both in the context of school shootings (Altheide, 2009b; Muschert, 2007; Schildkraut & Muschert, 2013) and alternative music (Sharman et al., 2022; Spracklen, 2018; Wright, 2000), there remains a surprising lack of focused research on how individual artists experience and respond to such crises through deliberate brand repositioning. This dissertation addresses that gap by examining Marilyn Manson not simply as a subject of media panic, but as an agent who navigated and manipulated public controversy in ways that reshaped his brand capital. In doing so, this research contributes a novel perspective to scholarship encompassing media outrage, celebrity image management, and cultural regulation.

Recent literature covering cancel culture highlights striking parallels to the mechanisms of a moral panic, particularly in the symbolic exclusion of individuals from cultural legitimacy through mass condemnation. Clark defines cancel culture as a mode of public accountability that involves “calling out” and removing figures whose behaviour is deemed socially harmful (2020, p. 89). While cancel culture research typically centres on social media-driven backlash (Janssens & Spreeuwenberg, 2022, p. 94), Manson’s case offers a valuable pre-digital precursor to contemporary cancellation—illustrating how legacy media played a central role in constructing reputational harm.

This dissertation employs a qualitative methodology, combining content analysis and media discourse analysis. First, Manson’s visual and lyrical output from both before and after Columbine will be examined to assess how his brand evolved in response to moral panic. Second, a comparative analysis of press coverage from mainstream and music-specific media outlets will evaluate how language and framing techniques shaped public perception. This dual approach allows for an integrated understanding of how Manson’s scapegoating was both produced by external forces and negotiated through his own branding interventions. To structure the investigation, this dissertation is organised into chapters: Chapter Two reviews key theoretical frameworks surrounding moral panic, media framing and celebrity branding. Chapter Three outlines the methodological design and analytic tools. Chapter Four undertakes the core analysis of Manson’s media portrayal and visual strategy. Chapter Five synthesises these insights to evaluate the implications of scapegoating, persona control, and mediated deviance. Together, this research aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how deviant celebrity is constructed, weaponised, and strategically contested in moments of cultural crisis.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Moral Panic Theory and the Construction of Deviance

The notion of moral panic, as theorised by Stanley Cohen, remains foundational to understanding the social construction of deviance. In his now canonical study of Mods and Rockers, Cohen defined a moral panic as an episode during which a person or group is determined as a threat to societal values, their deviance exaggerated by sensationalist media and public discourse. This model, anchored in a media-centric understanding of cultural control, presents the “folk devil” as both a symbolic enemy and a projection of collective anxiety (2011, p. 41).

In the third edition of his work, Cohen explicitly references the Columbine massacre as a paradigmatic instance of moral panic. He observes how the media swiftly mobilised a range of explanatory narratives—psychopathology, ideological extremism, gun culture—to make sense of the incomprehensible (2011, pp. 13-15). Crucially, Cohen identifies Columbine as a perceptual turning point in relation to school shootings: “a cognitive shift from ‘how could it happen in a place like this?’ to ‘it could happen anyplace’. In the USA at least, the Columbine Massacre signalled this shift” (2011, p. 14). This aligns directly with the central research question of this dissertation by positioning Columbine as the cultural rupture through which Marilyn Manson became intelligible as a scapegoat. Notably, Manson himself had already gestured towards the fickle and opportunistic dynamics of fame and public sentiment in his 1998 track The Dope Show:

“They love you when you’re on all the covers

When you’re not, then they love another” (Manson, 1998).

Although written prior to Columbine, these lyrics appear almost pre-emptive, encapsulating the rapid reversal of media affection into vilification that would follow in 1999, thereby reinforcing the logic of scapegoating central to moral panic discourse.

This shift in public consciousness did not remain confined to the American context. As Cohen further remarks, the global media reaction was telling: British tabloid headlines raced to impose narrative order, from ideological alarmism (“Disciples of Hitler”) to psychological reductionism (“The Misfits Who Killed For Kicks”), and even liberal critiques of gun culture (“The Massacre that Challenges America’s Love Affair with the Gun”) (2011, p. 14). Such interpretive chaos exemplifies Cohen’s core insight: “‘Over time these group formulated and group supported interpretations tend to override or replace individual idiosyncratic ones. They become part of the group myth, the collection of common opinions to which the member generally conforms.’” (Barker, as cited in Cohen, 2011, pp. 79-81). This global mythologising process was further examined by DeFoster (2010), who found that British editorial commentary in the decade following Columbine consistently framed school shootings through a lens of a distinctly American “frontier mentality”, suggesting a culturally embedded predisposition toward violence and individualism, further ingrained by a fascination with violent entertainment media (pp. 473-475). Her analysis supports Cohen’s argument through an illustration of foreign media’s construction of cohesive ideological narratives, which echoed and extended the original panic; turning Columbine into a symbolic site of American moral decline rather than treating it as a discrete event.

2.2. Media, Ideology, and the Making of a Scapegoat

Subsequent work by Goode and Ben-Yehuda (1994) introduced a set of criteria that render a moral panic empirically identifiable: concern, hostility, consensus and disproportionality (pp. 156-158). These recurring indicators have become widely adopted as a diagnostic framework for assessing panics across a range of cultural contexts (Critcher, 2008; Greer, 2010). However, their work has attracted criticism for its limited treatment of power dynamics, particularly the role of media institutions in shaping public sentiment. As Hall et al. (1978) observed in their study of mugging in 1970s Britain, moral panics are not spontaneous social eruptions, but often reflect the ideological interests of dominant groups. Goode and Ben-Yehuda’s model, though useful for classification, underemphasises how “mass media are credited with promoting MPs [moral panics] and contributing to exaggerated public fears that support social control efforts and public policy changes designed to reign in anti-social behavior associated with deviance, crime and social disorder” (Altheide, 2009a, p. 80). This criticism is especially pertinent to the case of Columbine, where mass media played a pivotal role in producing Marilyn Manson as a symbol of youth deviance.

Jeffrey Victor’s (1993) examination of the Satanic Panic offers a relevant antecedent. Victor emphasises the ideological utility of symbolic evil during moments of social uncertainty, noting: “research suggests that rumors usually arise in groups of people who are experiencing anxiety due to some sort of stress they share” (p. 47). Within this moral schema, figures like Manson become necessary antagonists—villains whose construction enables ideological closure. Victor’s analysis is particularly valuable in explaining how eschatological symbols (Satan, the Antichrist and (child) ritual abuse) are recycled through media discourse to generate affective coherence during times of cultural disorientation. While Hughes (2017) argues “the panic receded dramatically after 1990”, Manson wove nuances of these tales into his image and rehashes the legends by donning the persona of The Child Catcher. Manson makes use of overtly Satanic symbolism and addresses incendiary topics like child abuse in his second album, Smells Like Children (see Figure 3). By invoking these semiotic codes, media coverage of Columbine reanimated dormant anxieties and recontextualised Manson as an urgent danger.

Figure 3

Cover art for Marilyn Manson’s Smells Like Children (Cultice et al., 1995)

From this perspective, Manson’s status as a folk devil was not an arbitrary designation, but a product of cultural memory and media ritual. This correspondence reflects the central line of inquiry guiding this dissertation, which interrogates how Manson was positioned within moral panic discourse as a uniquely legible scapegoat. His visual presentation and lyrical content were not simply controversial; they were already discursively aligned with prior panics, making him a narratively efficient target.

2.3. Identity, Audience and the Politics of Panic

To complicate the classical model, Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) provides a more grounded account of how panic narratives function within in-group/out-group dynamics. The construction of the folk devil consolidates the moral majority’s self-image by positioning the “other” as a deviant outsider. The folk devil, in this schema, does not merely exist as a passive figure of revulsion; rather, they help consolidate the in-group by embodying what it is not.

However, as McRobbie and Thornton suggest, “So-called folk devils now produce their own media as a counter to what they perceive as the biased media of the mainstream” (1995, p. 568). This reflexivity is essential in the case of Marilyn Manson, who actively manipulated his media persona in response to panic discourses, using interviews, lyrics, and stage performance to reframe his vilification as part of a broader critique of American culture. His response to Columbine backlash, most notably his Rolling Stone op-ed (1999) and involvement in Bowling for Columbine (Moore, 2002), demonstrates that contemporary folk-devils are not merely constructed, but often complicit or resistant participants in their own mediation.

This performative contest over representation is echoed in the reactions of Manson’s fanbase. As Berres reflects, the post-Columbine backlash included not only public condemnation of Manson but also violent threats against self-identified goth and “Spooky Kids” (fans of Marilyn Manson named after the original band name: Marilyn Manson and the Spooky Kids) across the United States (2002, p. 46). These subcultural groups were scapegoated en masse, with media narratives implying that any trenchcoat-clad, heavy metal-listening adolescent might harbour murderous intent (Berres, 2002, p. 44). The panic did not distinguish between actual individuals and cultural signifiers; instead, it mobilised a symbolic economy in which deviance was visually encoded and publicly policed. This dynamic is crucial to the first subsidiary question of this dissertation, which investigates how audience identification and symbolic politics contribute to Manson’s role as scapegoat.

2.4. Media Reflexivity and the Evolution of Scapegoating

Digital media’s role in the evolution of moral panics cannot be overstated. Whereas earlier panics were filtered through centralised institutions—broadcast news, tabloids, official reports—contemporary episodes often emerge across decentralised platforms. As Walsh (2020b) contends “by promoting communications based on predicted popularity, [social media] prioritize and reward virality and the intensity of reaction rather than veracity or the public interest” (p. 845), enabling unprecedented diffusion and intensification of social alarm across digital networks.

While Manson’s case predated the rise of social media, his demonisation offers a proto-digital template: Wright (2000) identifies “What is striking about the recent ‘moral panic’ Marilyn Manson has inspired is that […] it seems to extend well beyond the predictable interests of the political right and the socioeconomic status quo it claims to represent” (p. 366), suggesting that Manson’s vilification foreshadowed hybrid trends across legacy and emergent media. This crossover context is crucial for understanding Manson’s treatment not only as a cultural scapegoat, but as an early test case for the logics of public shaming in the networked age.

2.5. Strategic Persona Management and Narrative Control

The construction of Marilyn Manson as a folk devil in the wake of Columbine exemplifies the symbolic economy of scapegoating central to moral panic theory. If moral panic theory offers a conceptual framework for collective overreaction, scapegoating reveals the narrative logic by which blame is directed, personified, and circulated. In this context, Manson became a cultural cipher—less a musician than a symbol of disintegrating moral order, projected into public consciousness via an orchestrated campaign of visual and discursive framing.

Media outlets seized on Manson’s carefully constructed persona, complete with Satanic overtones, pseudo-Nazi aesthetics [See Figures 4/5], and lyrics steeped in transgression, and repackaged it as a form of documentary evidence (Baddeley, 2000, p. 123). However, this framing was complicated by the facts. It is often stated, most notably by Cullen, that the Columbine shooters disliked Manson’s music and image (2024, p. 149). Yet Cullen’s authority, while influential, is not epistemically unproblematic. His book Columbine, written as a piece of literary journalism, blends investigative reporting with narrative techniques in ways that, as Morton (2014) argues, demand scrutiny regarding how narrative structures sustain truth-claims.

Figure 4/5

Left: Heinrich Himmler speaking at a Podium in Tirol, 1942. Right: Marilyn Manson performing “Beautiful People” at the MTV Video Music Awards, 1997.

Note. Figure 4 retrieved from https://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de/dba/de/search/?query=Bild+101III-Ege-240-10A

Note. Figure 5 retrieved from https://www.nachtkabarett.com/LogosAndSymbology/Shock

Langman’s (2025) comprehensive forensic analysis of available evidence suggests a more ambivalent reality. Eric Harris once referenced “M.M.” in a school assignment alongside Rammstein, KMFDM and Nine Inch Nails: bands he explicitly recommended for their lyrical content, implying that Manson was at least a peripheral influence. Dylan Klebold’s room contained a Marilyn Manson CD and a poster, and his mother confirmed that they had discussed his music. Friends noted that Dylan liked Manson’s work, even if Eric’s engagement appeared less consistent (pp. 1-2).

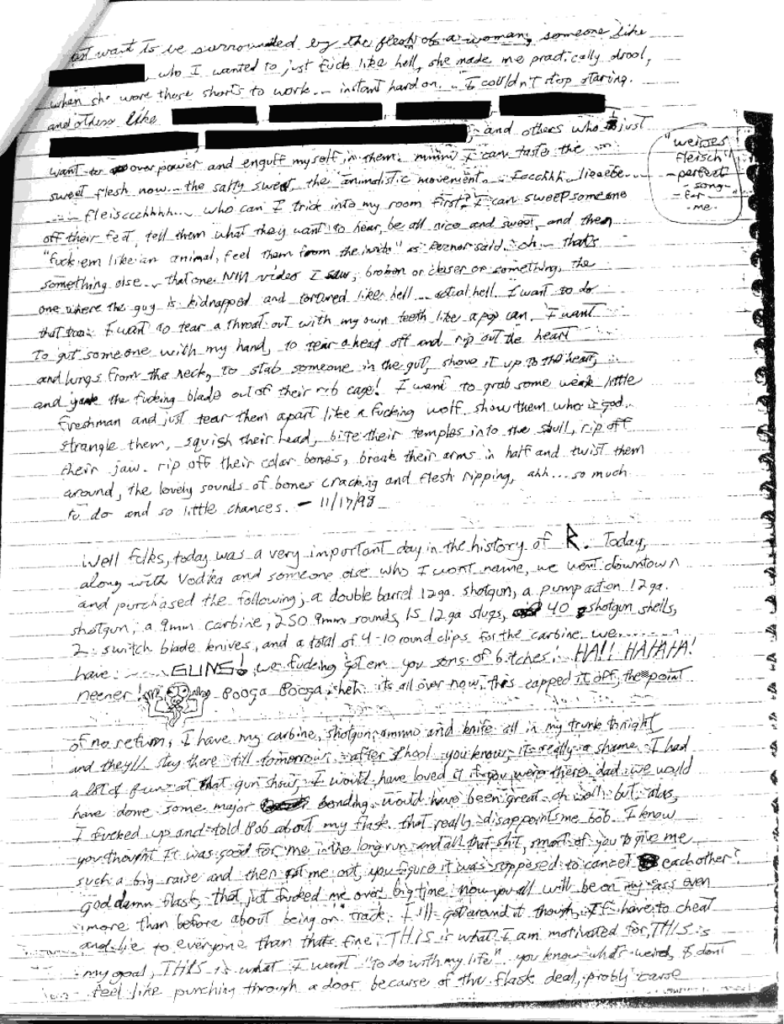

This suggests that while Manson was not central to their worldview, he was not entirely absent either. But the key point remains: there is no evidence of causality, only cultural proximity. In contrast, Eric Harris’s journals reveal a much stronger identification with German industrial metal, particularly bands KMFDM and Rammstein. In one entry, Harris describes the song Weißes Fleisch (Rammstein, 1995) as “perfect / song / for / me” (1998, Nov. 17) [See figure 6]. Another entry noted the coincidental symbolisation of KMFDM’s album Adios (1999), released the same day as the premeditated attack on Columbine:

“Heh, get this. KMFDM’s new album’s entitled “Adios” and its release date is in April. How fuckin appropriate, a subliminal final “Adios” tribute to Reb and Vodka, thanks KMFDM …I ripped the hell outa the system.” (1998, Dec. 12).

Figure 6

Excerpt from Columbine High School Shootings Investigations Records [Photocopy]. Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office (JC-001-026016).

Note. Retrieved from https://www.jeffco.us/3832/Columbine-Records

Thus, the media’s transformation of Manson into a moral scapegoat reveals more about societal mechanisms of blame than it does about the perpetrators themselves. Williams (2011) contends, even when media claims about youth subcultures and Manson’s music “turned out to be false”, they nevertheless “left a more lasting impression on the minds of news consumers than did concerns about how easily the boys had obtained the weapons they used in the attack” (p. 5). The urgency to locate evil in an aesthetic persona, rather than within the more chaotic, systemic and uncomfortable matrix of psychology, social dynamics and structural violence, demonstrates how folk devils operate: they simplify complexity and absorb cultural anxiety. As Grønstad (2008) asserts, “a threat of internal violence is restrained by the initiation of the scapegoating mechanism” (p. 54).

This process culminated in what Berres (2002) terms a “goth panic” (p. 44), whereby “any member of these black-clad legions could turn out to be the next school shooter” (p. 43). Despite the fact that neither Harris nor Klebold were self-identified goths or active participants of the subculture, “generally opposed to violence” (Frymer, 2009, p. 1395), the association of black clothing, alternative music and violent fantasy became a visual shorthand for deviance. “Goth” no longer functioned as a subcultural category, but instead as a floating signifier of pathology.

Such misreadings are emblematic of media scapegoating and mechanisms that conflate aesthetic rebellion with criminal intent. Hammond and Hundley (2020) substantiate how framing theory was used to codify metal fans as deviant others, associating their aesthetic with ‘’rebellion” and “corruption” denying them complexity or individuality (pp. 63-64). Their analysis reveals how legacy media utilised simplistic binaries—rational versus irrational, clean versus grotesque, safe versus transgressive—to uphold dominant value systems. The heavy metal fan, in this schema, is not simply misunderstood but actively produced as a threat.

These constructions are deeply classed. Brown and Griffin (2014) theorise that popular music criticism, especially publications NME, relies on symbolic violence to marginalise metal fans as “irredeemably lumpen… member[s] of a working class ‘mass’” (p. 732). Through language rich in irony, metal fandom is positioned as culturally illegitimate: frozen in time, aesthetically abject, and morally regressive. Manson’s fans became easy targets for this symbolic devolution. In the aftermath of Columbine, these classed and aesthetic prejudices resurfaced in mainstream discourse, not only to vilify Manson himself, but to alienate this audience as dangerous, deluded and culturally inferior. The stigma extended beyond the artist to those who identified with their message, reinforcing their marginal status through association.

This double movement renders artists like Manson uniquely vulnerable. His aesthetics were condemned not simply for being offensive, but for indexing an entire social category that elite media sought to exclude. Rather than investigate systemic failures, the media mobilised Manson’s persona as a site of symbolic resolution. As Deavours (2023) affirms, “symbolic annihilation is a systemic silencing of victims and takes power from those who have already had so much taken from them” (p. 1493), stressing how condemnation functions as a mechanism of exclusion rather than systemic critique.

In this light, Marilyn Manson’s treatment was not incidental but instrumental: he was scapegoated not because he caused the violence, but because he was culturally suited to absorb it. He notes the following:

“I remember hearing the initial reports from Littleton, that Harris and Klebold were wearing makeup and were dressed like Marilyn Manson, whom they obviously must worship, since they were dressed in black. Of course, speculation snowballed into making me the poster boy for everything that is bad in the world. These two idiots weren’t wearing makeup, and they weren’t dressed like me or like goths. Since Middle America has not heard of the music they did listen to (KMFDM and Rammstein, among [Cont. on 77] [Cont. from 24 others), the media picked something they thought was similar” (Marilyn Manson, 1999).

This retrospective analysis underscores the symbolic function he came to perform. Manson’s persona, already iconoclastic and aesthetically confrontational, became the screen onto which moral panic could be projected and culturally managed. His case, therefore, exemplifies how folk devils are mobilised not through evidence of harm, but through symbolic legibility within a dominant value system. In this sense, the post-Columbine treatment of Manson engages directly with the central research questions of this dissertation: to what extent does Marilyn Manson exemplify a cultural scapegoat during a moral panic? His case reveals how media framing mechanisms, amplified by classed and aesthetic biases, worked not only to vilify the artist but to discipline and marginalise his audience, reinforcing the broader structure of cultural exclusion and control.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This dissertation adopts a qualitative case study design to explore how Marilyn Manson was constructed as a cultural scapegoat during the moral panic following the Columbine High School shooting in 1999, and how he responded through strategies of brand management. A case study approach is appropriate because it enables an in-depth examination of a bounded cultural moment, allowing the researcher to investigate Marilyn Manson’s persona within its rich and specific socio-historical context; precisely the intended purpose of case study design (Yin, 2018, p. 5). Unlike comparative or large-scale content analyses, the case study foregrounds contextual complexity: Manson’s persona cannot be disentangled from the late-1990s media environment, broader anxieties about youth culture, and the longer genealogy of folk devil construction.

The qualitative orientation of this research rests on the recognition that meaning is socially produced and interpretatively mediated rather than objectively given (Ritchie & Lewis, 2013, p. 3). Thus, the methodology privileges discursive and symbolic analysis over numerical generalisation. The aim is not to test hypotheses in a positivist sense, but to illuminate processes of framing, reception, and strategic response that inform the relationship between celebrity, media, and moral panic.

3.2. Data Sources

The study analyses a range of primary cultural texts drawn from the period 1995-2003. This timeframe encompasses Manson’s breakthrough as a controversial public figure, the Columbine shooting (1999), and his subsequent attempts to reclaim narrative control. Data sources are organised into four categories:

- Lyrics and album artwork—particularly from Antichrist Superstar (1996), Mechanical Animals (1998) and Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) (2000), which were frequently cited in press coverage as indicative of Manson’s alleged nihilism (Osborne, p. 43). Lyrics function as texts through which symbolic associations of violence, alienation, and deviance were projected.

- Press coverage—including national newspapers, magazines, and televised news reports that directly linked Manson to Columbine or positioned him as emblematic of cultural decline. These provide insight into framing devices and discursive repertoires of scapegoating (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

- Manson’s own interventions—interviews, op-eds, and later autobiographical reflections, which reveal attempts at narrative re-authoring and brand repair.

- Public commentary—editorials, letters to the editor, and public discussion, which reflect audience uptake and the circulation of moral panic beyond elite media.

Together, these data provide a multi-layered corpus through which both media framings and counter-framings can be studied.

3.3. Selection Criteria

The decision to focus on Marilyn Manson derives from his centrality to the Columbine moral panic. Although other cultural scapegoats were invoked—video games, trench coats, and heavy metal (Hong et al., 2011, p. 864; Griffiths, 2010, p. 407; Hammond & Hundley, 2020, p. 66)—Manson’s persona summarised the anxieties of parents, politicians and media commentators (Frymer, 2009, p. 1399). His aesthetic and lyrical content provided a symbolic shorthand for deviance, making him an exemplary case of the “folk devil” in Cohen’s terms (2011, p. 41).

The selection of materials follows three principles:

- Relevance to crisis—texts must engage Manson explicitly in relation to Columbine or the broader discourse of youth violence.

- Temporal proximity—sources are drawn primarily from 1995-2003 to capture both the precipitating context and aftermath. Two sources fall outside this timeframe, included deliberately to provide a contemporary vantage point. These later reflections, one journalistic and one scholarly, offer insight into how Manson’s scapegoating has been retrospectively remembered and reinterpreted. Their inclusion enhances the study’s critical depth by situating Columbine not only as an immediate crisis but as a continuing cultural reference point.

- Diversity of perspective—data includes mainstream press, Manson’s own voice, and fan/public responses, to allow triangulation and avoid reproducing a one-sided narrative.

By delimiting the study in this way, the analysis remains manageable in scope while still attending to discursive variation.

3.4. Analytical Approach

Two complementary methods are employed:

3.4.1. Thematic Discourse Analysis

A thematic discourse analysis (TDA) identifies recurring patterns of meaning across the corpus. Following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase model (2006, p. 87), texts are coded for key discursive themes such as “Hostile”, “Neutral” and “Defensive” (Appendix, Table A1). These themes are then contextualised through media framing theory (Goffman, 1986; Entman, 1993) and Snow et al.’s later notion of frame alignment (1986). The objective is to show how Manson was not simply described but narratively positioned within a wider economy of fear and blame.

3.4.2. Semiotic Analysis

Because Manson’s public persona relied heavily on visual symbolism, album artwork, stage costumes and performance aesthetics, a semiotic analysis complements the discourse work. Drawing on Barthes’ distinction between denotation and connotation (1968, p. 91), images are examined for their signifying practices (Appendix, Table A4). This method foregrounds how visual texts functioned as “evidence” within media moralisation, and Manson later re-deployed these signifiers to challenge or subvert dominant narratives.

Integrating TDA and semiotics allows the dissertation to capture both linguistic and visual registers of meaning, recognising that Manson’s scandal was mediated through an interplay of words, images, and performance.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This project does not involve human participants and therefore poses minimal ethical risk. Nonetheless, certain considerations are acknowledged in accordance with recommendations provided by the AoIR Ethics Committee (Markham & Buchanan, 2012, pp. 4-11):

- Representation of tragedy—Columbine remains a traumatic event, and care has been taken to avoid sensationalism or exploitation. Texts are discussed for their cultural significance rather than to revisit the violence itself.

- Interpretive bias—qualitative research is unavoidably shaped by the positionality of the researcher. Reflexivity is therefore emphasised, with analytical decisions made transparent and claims supported through direct textual evidence rather than conjecture.

- Secondary data ethics—while all materials are publicly available, sensitivity is exercised when citing victim narratives or survivor accounts, ensuring that their words are not instrumentalised beyond their original context.

By explicitly addressing these issues, the methodology aims to maintain scholarly integrity while respecting the gravity of the subject matter.

3.6. Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the focus on one figure, while analytically rich, may restrict broader generalisability. Manson is a particularly flamboyant and polarising case; as such, the extent to which his experience reflects wider patterns of celebrity scapegoating requires careful qualification. Second, archival availability shapes the corpus: certain online fan discussions and televised broadcasts are no longer accessible, potentially skewing representation. Third, the interpretative nature of discourse and semiotic analysis means that findings are contingent rather than definitive. However, these limitations are intrinsic to qualitative research and are mitigated by methodological transparency and triangulation of sources.

4. Analysis

This chapter presents the findings of a thematic discourse and semiotic analysis of sources concerning Marilyn Manson, covering primarily the period 1995-2003 but including two later retrospective accounts (Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 69; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 70) to demonstrate the persistence of scapegoating narratives in cultural memory. The aim is to show not only how Manson was represented but how he was narratively positioned as a folk devil within a wider economy of fear, blame, and cultural regulation.

The analysis follows Braun and Clarke’s six-phase model of thematic discourse analysis (TDA) (2006, p. 87). Each text was coded according to tone (Hostile, Neutral, Critical, Defensive) using the project Codebook for Tone Categorisation (Appendix, Table A1). This process ensured consistency in identifying how each source positioned Manson in relation to Columbine and broader debates. Each source was then coded for thematic content, producing six recurring patterns across the corpus: Moral Decline, Youth Panic, Satanism & Scapegoating, Celebrity Deviance, Media Blame & Hysteria, and Gun Politics. These are defined in the Thematic Codebook (Appendix, Table A2). Together, the Source Log (Appendix, Table A3) provides the full evidential record of this process, listing all items with bibliographic detail, tone assignment, thematic classification, and illustrative quotations.

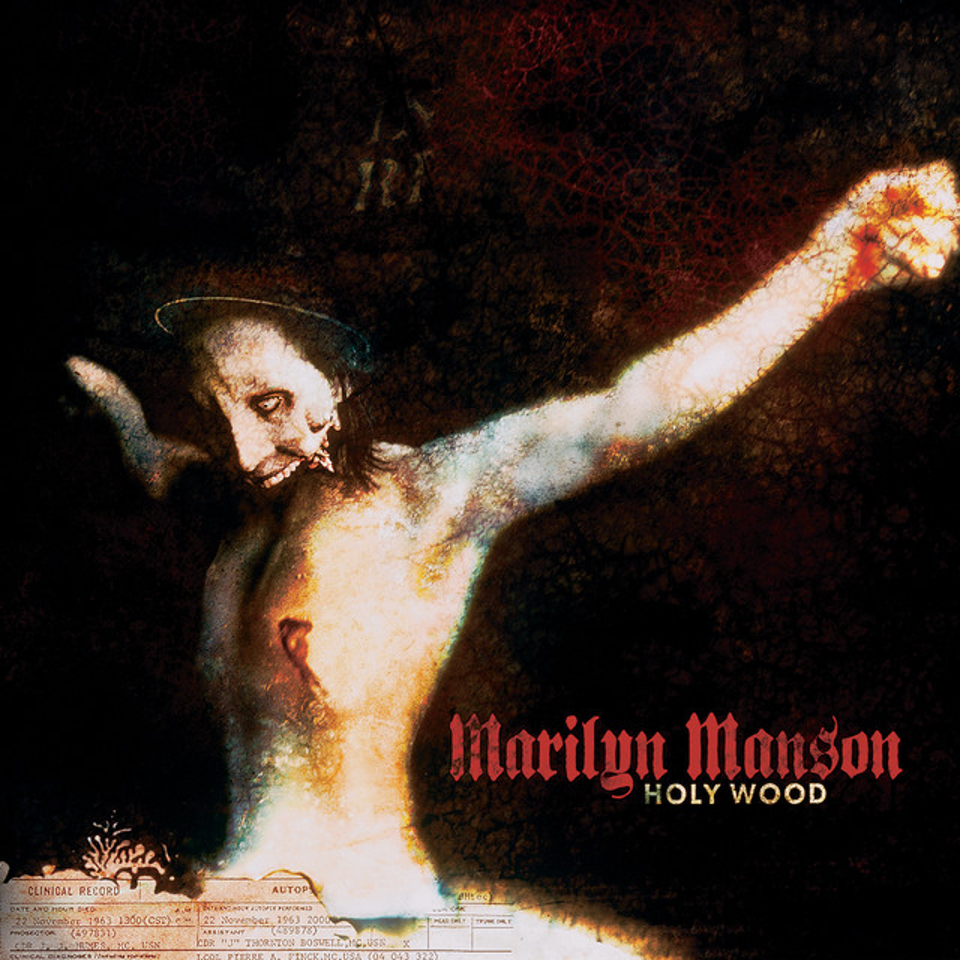

Because Manson’s persona relies heavily on visual symbolism, including artwork, stage costumes, and performance aesthetics, a semiotic analysis complements the discourse work. Employing Barthes’ (1968) distinction between denotation (the literal, descriptive level of an image) and connotation (the cultural meanings attached to it) (p. 91), the analysis examines how images functioned as “evidence” in hostile framings as counter-symbols in defensive rebranding, as shown in the Image Log (Appendix, Table A4). For instance, the Antichrist Superstar album front cover (Brown, 1996; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 2) was denotatively a distorted portrait, but connotatively mobilised as proof of satanism; conversely, Holy Wood (Figure 7; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 7) redeployed crucifixion imagery to frame Manson as a martyr of media hysteria.

Figure 7

Front Cover Art for Marilyn Manson’s Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) (Brown, 2000; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 7)

The sections that follow are organised by tone categories—Hostile, Neutral, Critical, Defensive—with each subsection highlighting the thematic patterns and semiotic strategies that recur across the dataset. In doing so, the chapter demonstrates that Manson’s post-Columbine treatment was not incidental, but structured through powerful cultural narratives of deviance, panic, and blame, and that his own interventions strategically contested these narratives. Supporting evidence, including coded excerpts from the Source Log, Tone and Theme codebooks, and image interpretations, is provided in the appendices to ensure methodological transparency.

4.1. Hostile Framings: Constructing the Folk Devil

Hostile framings (n=23; (see Appendix, Table A3) exemplify Cohen’s (2011) “folk devil” dynamic, portraying Manson not simply as controversial but as an existential threat to moral order. According to the Tone Codebook (Appendix, Table A1), these sources adopt overtly negative stances, frequently mobilising discourses of morality, religion, and youth protection to cast him as the embodiment of cultural decay.

4.1.1. Thematic Discourse Analysis

Three interlinked themes recur across hostile coverage:

- Moral Decline. Many accounts presented Manson as symptomatic of social collapse rather than an isolated cultural irritant. A Richmond Times-Dispatch piece asked:

“What is the world coming to when this is what we endorse? When this band’s vileness is what we allow our children to purchase, and listen to, and become influenced by? When we spend hard-earned bucks to support a band whose members are named after entertainment figures and serial killers, who perform lewd sex acts on stage, who sing words such as, ”I am the ism, my hate’s a prism. Let’s just kill everyone and let your God sort them out”?” (Ruggieri, 1996; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 7)

Here, Manson is not merely criticised for his lyrics but framed as symptomatic of civilisational decay. The rhetorical questions present him as a threat to children, a debasement of popular culture, and a marker of declining moral order. In this way, hostile framings collapsed Columbine into a broader cultural narrative of breakdown and decadence. Table 2 illustrates how hostile outlets repeatedly mobilised overlapping themes of Moral Decline, Satanism & Scapegoating, and Youth Panic, framing Manson as a convenient vessel of cultural decay.

Table 2

Hostile Quote Excerpts by Theme

| ID | Author | Outlet | Date | Type | Key Quote | Primary Frame |

| 7 | Ruggieri, M. | Richmond Times-Dispatch | 24/10/1996 | Opinion | “What is the world coming to when this band’s vileness is what we allow our children to purchase, and listen to, and become influenced by?” | Moral Decline |

| 8 | Uknown | Tampa Tribune | 13/11/1996 | Editorial | “This is hard-core aggressive industrial rock… bondage, S&M, body piercing and satanic imagery.” | Moral Decline; Youth Panic |

| 9 | Simpson, C. | The Herald (Glasgow) | 10/12/1996 | News article | “Faced with the imminent arrival of the notorious American rock band Marilyn Manson, the presbytery’s mission committee has called on Christians to pray for God’s protection over the city.” | Satanism & Scapegoating; Youth Panic |

| 10 | Lieberman, J. (Sen.), Bennett, W., Tucker, C. D., & Lezar, T. | FDCH Political Transcripts | 10/12/1996 | Policy transcript | “One of the artists that MCA is now using its might to market deserves special mention, and that is shock-rocker Marilyn Manson… This is perhaps the sickest group ever promoted by a mainstream record company.” | Moral Decline; Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 12 | Mervis, S. | Pittsburgh Post-Gazette | 14/02/1997 | Feature | “Marilyn Manson is currently on a national tour to destroy Christianity and bring about the apocalypse.” | Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 22 | Unknown | BBC News | 21/04/1999 | News article | “This group… is variously described as being obsessed with guns, Nazis, the military, the Internet, rock singer Marilyn Manson and goth-rock culture.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 23 | Fisher, M. | Ottawa Citizen | 21/04/1999 | News article | “The group often talked in class about decapitating people and often sing and quote Marilyn Manson songs.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 24 | Sawyer, D. & Donaldson, S. | ABC News (20/20) | 21/04/1999 | News transcript | “Were they part of a nationwide trend — angry teenagers obsessed with Hitler and the bizarre underground rock singer Marilyn Manson?” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 25 | Ross, B., Sawyer, D. & Donaldson, S. | ABC News (20/20) | 21/04/1999 | News transcript | “What was interesting… in his living room he had Nazi swastikas… I think in his case, you can trace it right back to Marilyn Manson.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 26 | Gales, A. | Press Association | 21/04/1999 | News article | “It appears you have a bunch of kids who’ve been into black metal music – Marilyn Manson – who basically have apocalyptic fantasies and (who operate under) a heavy code of neo-Nazism.” | Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 27 | McDowell, R. | Associated Press | 21/04/1999 | News article | “They are called the ‘Trench Coat Mafia,’ a group of about 10 students who wear long black coats, keep to themselves and follow shock rocker Marilyn Manson.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 28 | Atkinson, S. | Daily Record (Scotland) | 21/04/1999 | News article | “The Trench Coat Mafia were devoted fans of controversial singer Marilyn Manson.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 30 | Nelson, C. | VH1 | 22/04/1999 | News feature | “Marilyn Manson had fans as young as 12 ‘under his control’… I think he promotes it and can be part of the blame.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 31 | Unknown | The Journal (Newcastle, UK) | 22/04/1999 | News article | “However, classmates of the duo pointed to more sinister interests and one pupil said: “They sing Marilyn Manson songs and joke about killing people. They’re into Nazis. They take pride in Hitler. They’re really, really creepy.”” | Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 32 | Worrall, B. | Birmingham Post | 22/04/1999 | News article | “The teenage gunmen who killed 13 people in the Colorado school massacre were obsessed with the occult, mutilation and Hitler. The pair, who shot themselves after the carnage, were part of a self-styled “Trenchcoat Mafia” gang and fans of controversial cult singer Marilyn Manson.” | Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 33 | Unknown | Western Daily Press | 22/04/1999 | News article | “We are now seeing a new form of extremism, taking extreme music and mixing it with far-right ideologies… confirmed by the Denver killers’ obsession with Marilyn Manson.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 34 | Garfinkel, D. | The Sun (UK) | 22/04/1999 | News article | “Manson’s band belongs to a San Francisco church which worships Satan. He has boasted: ‘In my eyes, evil is good.’” | Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 36 | O’Connor, C. | MTV News | 26/04/1999 | News article | “Sen. Joseph Lieberman and William Bennett pointed to Manson’s music… as contributing factors in the massacre.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 38 | Kirtz, J. | Fox News | 28/04/1999 | News transcript | “Senator Sam Brownback has made sure the violent lyrics of rock star Marilyn Manson are now in the Congressional Record.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Moral Decline |

| 41 | Dominguez, C. | NBC News | 29/04/1999 | News transcript | “Critics have been so outspoken that the performer has now canceled the remaining dates of a US concert tour.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 51 | Shriver, M & Corderi, V. | NBC News / Dateline | 12/12/1999 | News transcript | “This is the music causing concern these days: the aggressive sounds and ghoulish images, disturbing lyrics of Marilyn Manson…” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Moral Decline |

| 54 | Mooney, A. | The Mirror | 10/11/2000 | News article | “She is obsessed with death and is always talking about suicide… She told me ‘Blood is good’.” | Satanism & Scapegoating; Youth Panic |

| 62 | D’Angelo, J. | MTV News | 17/05/2001 | News article | “The group objects to Manson’s promotion of ‘hate, violence, death, suicide, drug use, and the attitudes and actions of the Columbine High School killers.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Moral Decline |

Note. Adapted from Source Log (Appendix, Table A3)

- Youth Panic. Adolescents were framed as endangered or corrupted. Tabloid reports proclaimed “Killers Worshipped Rock Freak Manson: School Massacre on Hitler’s Birthday” (Garfinkel, 1999; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 34). Emphasising the vulnerability of teenagers to malign influence.

- Satanism & Scapegoating. Religious rhetoric played a central role in hostile framings, casting Manson as demonic and spiritually dangerous. One striking example came from The Herald (Glasgow), which responded to Manson’s tour with the following appeal:

“Faced with the imminent arrival of the notorious American rock band Marilyn Manson, the presbytery’s mission committee has called on Christians to pray for “God’s protection over the city and particularly its young people”” (Simpson, 1996; Appendix, Table A3, Source log ID 9)

Here, Manson is not framed as a controversial performer but as a literal spiritual threat, requiring divine protection against his corruptive influence. The appeal to communal prayer positioned him as a satanic figure, reinforcing the scapegoating mechanism by portraying him as the moral opposite of stability and purity.

4.1.2. Semiotic Analysis

Beyond isolated publicity photographs, hostile framings drew upon Manson’s broader iconographic system. The Antichrist Superstar back cover (Figure 8; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 3) features Manson’s portrait accompanied by the circular “shock” logo, a design bisected by a lightning bolt with an arrowhead, surrounded by occult sigils (as also seen in Figure 9); connotatively, hostile readings recorded these symbols as proof of satanic allegiance. The logo’s resemblance to the Nazi blitz insignia, alongside its similarity to electrical hazard symbols, enabled critics to depict Manson as promoting both nihilism and authoritarian danger.

Figure 8/9

Left: Antichrist Superstar back cover featuring the shock logo (Brown, 1996; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 3). Right: The Satanic Mass front cover featuring the Sigil of Baphomet (Church of Satan, 1967).

Note. Figure 9 retrieved from https://churchofsatan.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/SatanicMass.jpg

Hostile framings often relied on visual comparisons to reinforce satanic associations. The front album cover of The Satanic Mass (1967), recorded by the Church of Satan, predominantly displays the Sigil of Baphomet (Figure 9). Denominatively, the symbol presents a goat’s head within a pentagram, encircled by Hebrew lettering spelling Leviathan (לִוְיָתָ). Connotatively, it has long functioned as the official emblem of the Church of Satan, codifying the organisation’s philosophy of inversion and opposition. Because of its entrenched cultural resonance, references to the sigil worked as shorthand for spiritual corruption and satanic danger.

The School Crossing Guard promotional photograph (Figure 10; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 13) was stripped of irony. Denotatively, a symbol of child safety, its hostile recontextualisation transposed meaning: the figure intended to protect children instead signified menace. The image reinforced Youth Panic discourses by visually transforming ideas of child safeguarding into child endangerment.

Figure 10

School Crossing Guard promotional photograph (Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 13).

Note. Retrieved from https://manson.wiki/File:School_Crossing_Guard.jpg

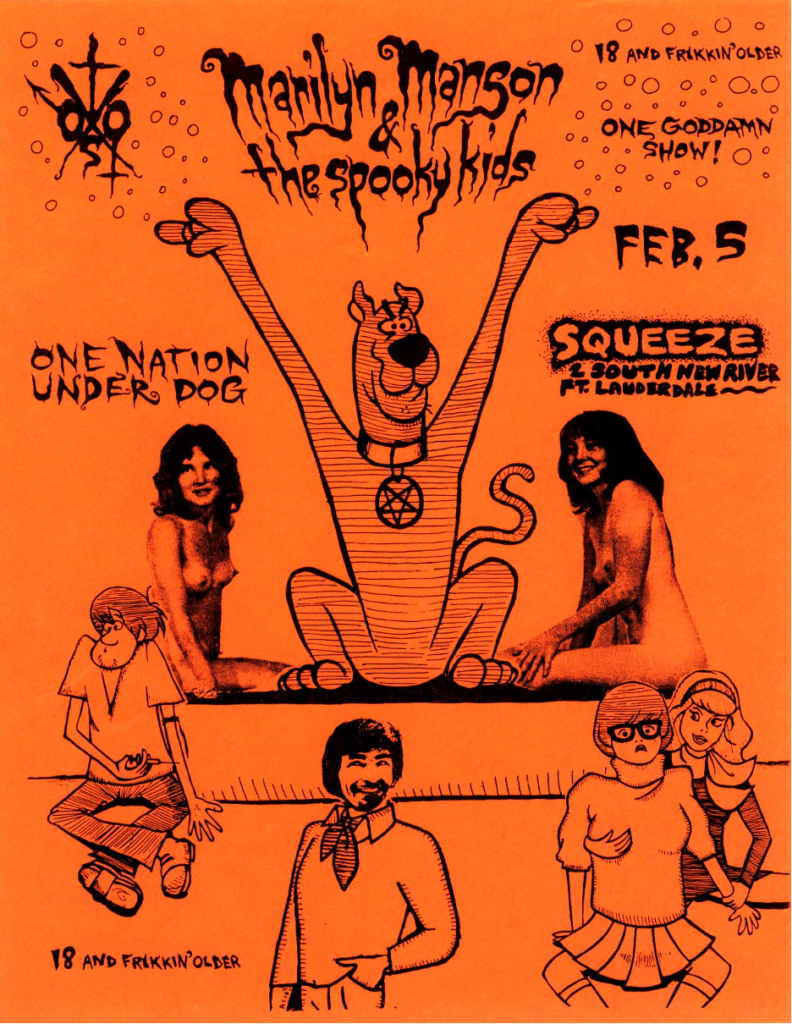

Similarly, The Spooky Kids promotional flyer (Figure 11; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 11) collages Scooby-Doo characters, lesbian sexual innuendo, drug imagery and Charles Manson’s face, with Scooby marked by a pentagram. Connotatively, these juxtapositions symbolised corruption of innocence, satanic parody, and the collapse of moral order. While originally designed as satirical promotion, hostile readings could easily reframe the flyer as “evidence” of Moral Decline and Youth Panic, as cartoon innocence was contrasted with obscenity.

Figure 11

Marilyn Manson and The Spooky Kids flyer (Unknown, n.d.; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 11).

Note. Retrieved from https://www.spookykids.net/indexxx.html

4.1.3 Persistence of Hostility

Hostile framings persisted retrospectively. Brannigan’s piece “Columbine: How Marilyn Manson Became Mainstream Media’s Scapegoat” (2020; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 70) reasserts that the shooters disliked Manson, but by revisiting the claim, reinscribes him into Columbine discourse. This demonstrates the durability of scapegoating themes beyond the immediate crisis.

4.2 Critical Framings: Reflexivity and Context

Critical framings (n=9) offered reflexive distance, situating Manson’s vilification within media processes rather than attributing causality. According to the Tone Codebook (Appendix, Table A1), these sources critically evaluated cultural dynamics instead of condemning or defending. Extracts illustrating these dynamics are collated in Table 3, establishing the manner in which critical framings simultaneously distanced themselves from panic while reproducing aspects of its logic.

Table 3

Critical Quote Excerpts by Theme

| ID | Author | Outlet | Date | Type | Key Quote | Primary Frame |

| 11 | Strauss, N. | Rolling Stone | 23/01/1997 | Interview | “There are two things that Marilyn Manson has been designed to do: speak to the people who understand it and scare the people who don’t.” | Satanism & Scapegoating; Moral Decline |

| 15 | Sterngold, J | The New York Times | 01/12/1997 | Feature | “The antics of Marilyn Manson helped spark the drive for concert ratings.” | Moral Decline |

| 29 | Merida, K. & Leiby, R. | Washington Post | 22/04/1999 | News article | “Before teenagers commit violence, they witness it in American culture.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Moral Decline |

| 35 | Noonan, P. | Wall Street Journal (Europe) | 23/04/1999 | Opinion / commentary | “What walked into Columbine High School Tuesday was the culture of death… This time it wore black trench coats.” | Moral Decline |

| 43 | Lepage, M. | The Gazette (Montreal) | 01/05/1999 | Feature | “Did Manson’s music have the power to poison their souls? Perhaps, but they still needed a TEC DC-9 to do the dirty work.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Gun Politics |

| 49 | Unknown | Chicago Tribune | 06/07/1999 | Letter to the editor | “I believe that the cause of all the controversy of this shooting and the shooting itself is the media and today’s society.” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 51 | Marshall, A | The Independent | 18/08/1999 | News article | “There was a hysterical move to blame the US pop star Marilyn Manson, even though there was little evidence that his music had anything to do with the event.” | Moral Decline; Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 53 | U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce | Hearing Before The Committee On Commerce, Science, And Transportation United States Senate One Hundred Sixth Congress Second Session | 13/09/2000 | Policy hearing | “The problem is not one industry, but can be found in virtually every form of entertainment: movies, music, and video and PC games. Together, they take up the majority of a child’s leisure hours. And the messages they get, and images they see, often glamorize brutality, and trivialize cruelty.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Moral Decline |

| 61 | Unknown | Billboard | 07/05/2001 | News article | “The church-affiliated group Citizens for Peace and Respect says Manson promotes violence, hate, and drugs, and should not spread his message in Denver.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Youth Panic |

Note. Adapted from Source Log (Appendix, Table A3)

4.2.1 Thematic Discourse Analysis

Two themes dominate critical sources:

- Media Blame & Hysteria. Critical political and journalistic sources frequently argued that sensationalism and cultural scapegoating, rather than Manson himself, fuelled the panic. For instance, S. HRG. 106–1144 Marketing Violence To Children (U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, 2000; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 53) drew attention to the marketing of violent music, asserting:

“Studies show that modern music lyrics, in particular, have become increasingly misogynistic. Hatred and violence against women are widespread and unmistakable in mainstream hip-hop and alternative music.”

Although framed as a critique of the industry as a whole, this statement illustrates how the panic surrounding Manson was folded into a broader narrative of media blame and moral decline. Rather than treating Columbine as an isolated act of violence, congressional discourse positioned music genres as catalysts of cultural decay, with Manson functioning as a symbolic shorthand for the alleged glamourisation of violence, In doing so, political commentary echoed journalistic hysteria, amplifying the scapegoating mechanism by embedding it within state-level discourse.

- Moral Decline. Critical framings often emulated panic logic even while contextualising Manson. For example, Rolling Stone’s “Sympathy for the Devil” interview (Strauss, 1997; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 11) presented him as a complex artist yet still embedded his persona within narratives of excess and cultural decay, reinforcing his symbolic link to moral decline.

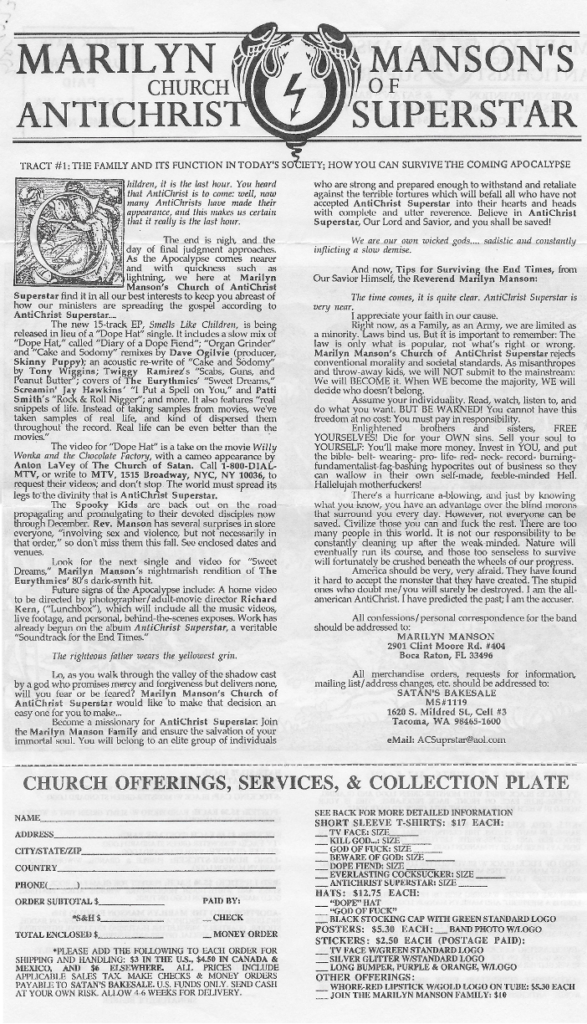

4.2.2 Semiotic Analysis

Critical framings also drew on imagery, though often with reflexive intent. The Church of the Antichrist Superstar pamphlet (Figure 12; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 15) exemplifies this. Denotatively mimicking evangelical tracts, it connotatively satirised the moral panic surrounding Manson. Yet, even when the pamphlet is used to contextualise hysteria, the contiguity of “church” and “antichrist” continues to trigger associations of spiritual decline. Thus, attempts at critique risked reinscribing Moral Decline cues.

Figure 12

Church of the Antichrist Superstar pamphlet (Unknown, n.d.; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 15).

Note. Retrieved from https://manson.wiki/File:ChurchOfAntichristSuperstarFrontTopHalf.jpg

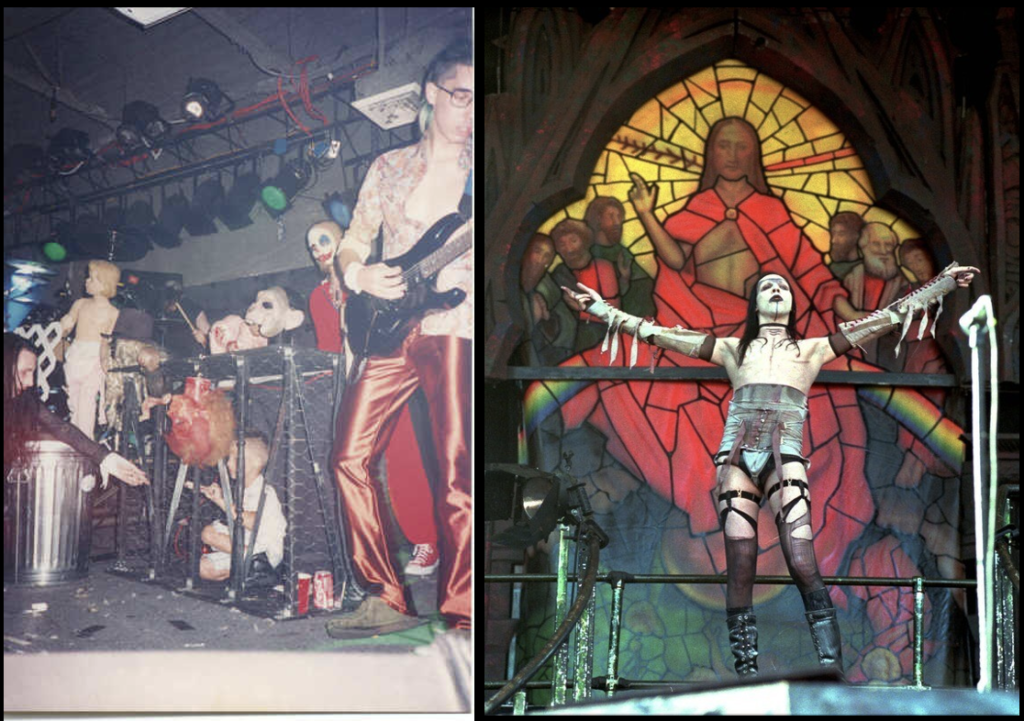

Concert photography reinforced this paradox. One depiction of The Spooky Kids in concert (Figure 13; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 12) is theatrical in composition: Manson leans in over a rubbish bin toward a child inside a cage, surrounded by a shirtless mannequin, a severed doll head, and circus masks. Denotatively, the image records a stage set built on shock value; connotatively, it mobilises themes of childhood innocence distorted and endangered. The cage, toys, and grotesque décor counterpose play with menace, producing an unsettling parody of youth culture. In parallel, the 1997 performance image (Figure 14; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 5) situates Manson before a stained glass backdrop of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement , arms outstretched in a crucifix-like pose and dressed in a corset with torn sleeves. Denotatively, the fetish costume and Christian iconography transgress sacred boundaries. This staging echoed the same cultural triggers mobilised in neutral accounts: endangered youth, moral decline, and corrupted innocence.

Figure 13/14

Left: Spooky Kids Concert Image (Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 12). Right: Marilyn Manson performing in front of stained glass backdrop of the Last Judgement, 1997 (Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 5).

Note. Figure 13 retrieved from https://www.spookykids.net/pictures/live/live05.jpg

Note. Figure 14 retrieved from http://www.nachtkabarett.com/ihvh/img/manson_godform.jpg

For subcultural audiences, such imagery functioned as satire (Blake, 2009), lampooning American anxieties about morality, religion, and childhood. Yet once photographs circulated beyond concert spaces, their meanings were reconfigured. Detached from context, both the caged child and crucifix-like pose became ready-made symbols of cultural corruption, amplifying existing narratives that linked Manson to Moral Decline and Youth Panic.

This process mirrors the mechanisms described by Victor (1993), who traces the ways in which the Satanic Panic repeatedly drew upon tropes of endangered children to anchor diffuse anxieties (p. 103). By invoking the same imagery—children in danger, religion inverted—the photographs resonated with a cultural script already primed for moral alarm. McRobbie and Thornton (1995) maintain:

“For, in turning youth into news, mass media both frame subcultures as major events and disseminate them; a tabloid front page is frequently a self-fulfilling prophecy” (p. 565).

Semiotic analysis of performance photographs, therefore, underscores how Manson’s visual repertoire sustained panic discourses indirectly: even absent from narration, his aesthetics contextualise why Columbine-era coverage could so readily catalyse irony into menace and parody into proof.

4.3 Neutral Framings: Reporting Without Moralising

Neutral framings (n=5) aimed to report events but often carried implicit evaluative weight. According to the Tone Codebook (Appendix, Table A1), these sources avoided explicit judgement but nonetheless positioned Manson within crisis narratives.

4.3.1 Thematic Discourse Analysis

Two themes dominate neutral coverage:

- Moral Decline. Factual reporting often highlighted “public outrage”, implicitly citing Manson as a cultural problem. For example, BBC News reported that “Eric Harris, 18, and Dylan Klebold, 17, who killed 13 people at the Denver school before dying of gunshot wounds themselves, were believed to have been Marilyn Manson fans. Some believe Manson’s song lyrics may have influenced the teenagers” (Unknown, 1999; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 40).

- Youth Panic. Cancellations were framed as measures to protect adolescents. New York Times coverage (Unknown, 1999; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 42) emphasised the susceptibility of young audiences, subtly reinforcing the logic of danger.

Even ostensibly neutral reporting sustained panic cues through word choice and event framing. As shown in Table 4, neutral references repeatedly foregrounded Manson’s alleged connection to Columbine while withholding contextual detail.

Table 4

Neutral Quote Excerpts by Theme

| ID | Author | Outlet | Date | Type | Key Quote | Primary Frame |

| 21 | Clinton, W.J. | The American Presidency Project | 20/04/1999 | Commentary / political speech | “We must do more to reach out to our children and teach them to express their anger and to resolve their conflicts with words, not weapons.” | Youth Panic; Gun Politics |

| 39 | Sterngold, James | The New York Times | 29/04/1999 | News article | “The cancellations come after protests outside Manson concerts and concerns about violent imagery in music after the Columbine shootings.” | Media Blame & Hyseria; Youth Panic |

| 40 | Unknown | BBC News | 29/04/1999 | Press report | “But Manson has condemned the media for linking his band, also called Marilyn Manson, to the shootings.” | Media blame & Hyseria; Gun Politics |

| 42 | Unknown | The New York Times | 30/04/1999 | Public Commentary | “People blame music and video games and all these outside influences as scapegoats.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 69 | France, L.R. | CNN | 20/04/2009 | News feature | “Shock rocker Marilyn Manson weathered speculation that his songs may have influenced the pair of young murderers. He addressed the issue in a Rolling Stone magazine article in 1999.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Youth Panic |

Note. Adapted from Source Log (Appendix, Table A3)

4.3.2 Semiotic Analysis

What stands out in the aftermath of Columbine is not Manson’s disappearance from public life however, but his continued visibility. Far from being erased by panic, he remained a focal point of fascination, demonstrating how notoriety could be converted into cultural capital. This resilience reflects the success of his counter-framing: by embracing transgression and casting scandal as performance, Manson ensured that even framings intended to neutralise or defend his presence nonetheless contributed to his ongoing visibility.

The 2000 MTV studio photograph (Fgure 15; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 8) evinces this dynamic. Denotatively, it records a promotional appearance alongside mainstream host Carson Daly, encircled by a multitude of fans with outstretched arms. Connotatively, the proximity consolidates the paradox of Manson’s image: corpse-like makeup paired with a black and white trench coat signal transgression, while Daly embodies the institutional embrace of MTV. The effect is incorporation rather than marginalisation; Manson simultaneously appears as a folk devil and pop spectacle.

Figure 15

Marilyn Manson and Carson Daly outside the MTV studios in New York for an episode of TRL during ‘Spankin New Music Week’, 2000 (Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 8).

Note. Retrieved from https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/marilyn-manson-and-carson-daly-outside-the-mtv-studios-in-news-photo/2279143?adppopup=true

The intensity of fan devotion confirms that Manson remained a figure of fascination even amid cultural controversy. The gestures of reaching hands recall religious iconography of veneration, echoing press disquietudes of youth susceptibility. Yet these same gestures testify to his ongoing appeal. Just as neutral and defensive reporting reproduced cues of Youth Panic and Moral Decline while withholding overt moralisation. By this means the image substantiates the operation of neutral framings: rather than removing him from view, they positioned Manson as a contested but unavoidable presence in public life, enhancing his cultural centrality post-Columbine.

This dichotomy aligns with Thornton’s (1995) concept of subcultural capital (p. 11), where deviance functions as a resource both within subcultures and when translated into mainstream contexts. McRobbie (1994) similarly monitors how subcultural forms are commodified as spectacle, retaining their charge while serving wider cultural economies (p. 190). Neutral framings of Manson interacting with fans reflect this process, underscoring his critique of Celebrity Deviance: scandal and popularity are not opposites but mutually reinforcing elements in the production of cultural visibility.

4.4 Defensive Framings: Counter-Branding and Narrative Reclamation

Defensive framings (n=33) captured Manson’s own interventions and sympathetic accounts. According to the Tone Codebook (Appendix, Table A1), these reject scapegoating and often redirect attention to structural issues. The array of perspectives underpinning these framings is demonstrated in Table 5, which provides further context for the analysis below.

Table 5

Defensive Quote Excerpts by Theme

| ID | Author | Outlet | Date | Type | Key Quote | Primary Frame |

| 1 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 24/10/1995 | Album / Lyrics | “Sweet dreams are made of this… Everybody’s looking for something.” | Celebrity Deviance |

| 2 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 24/10/1995 | Album / Lyrics | “’Cause I AM the all-American Antichrist… I’m a rock & roll nigger.” | Moral Decline |

| 3 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 8/10/ 1996 | Album / Lyrics | “The weak ones are there to justify the strong.” | Moral Decline |

| 4 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 9/10/ 1996 | Album / Lyrics | “Our Antichrist is almost here…” | Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 5 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 10/10/1996 | Album / Lyrics | “I went to god just to see, and I was looking at me… when I’m god everybody dies.” | Moral Decline |

| 6 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 11/10/1996 | Album / Lyrics | “The boy that you loved is the man that you fear.” | Youth Panic |

| 13 | Mervis, S. | Pittsburgh Post-Gazette | 02/05/1997 | Feature | “We’re in the front lines of the war fighting for our First Amendment right to perform.” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 14 | Unknown | NYROCK | 08/ 1997 | Interview | “Do you feel responsible if your fans go to such extremes? … I don’t think anybody would feel responsible if I slit my wrists.” | Youth Panic |

| 16 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 15/09/1998 | Album / Lyrics | “We’re all stars now, in the dope show.” | Celebrity Deviance |

| 17 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 16/09/1998 | Album / Lyrics | “Rock is deader than dead.” | Moral Decline |

| 18 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 17/09/1998 | Album / Lyrics | “I don’t like the drugs, but the drugs like me.” | Moral Decline |

| 19 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 18/09/1998 | Album / Lyrics | “A pill to make you numb, a pill to make you dumb…” | Youth Panic |

| 20 | Lowe, S. | Select | 03/ 1999 | Interview | “In a situation like that, you have parents who are very upset wanting to point a finger at someone… they are always reluctant to point it at themselves.” | Media Blame; Celebrity Deviance |

| 37 | Unknown | MTV News | 28/04/1999 | Press release | “The media has unfairly scapegoated the music industry and so-called Goth kids… This tragedy was a product of ignorance, hatred, and an access to guns.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Gun Politics |

| 44 | Marilyn Manson | Rolling Stone | 28/05/1999 | Op-ed | “Speculation snowballed into making me the poster boy for everything that is bad in the world.” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 45 | Unknown | Kerrang! | 06/ 1999 | Interview | “What happened in America is exactly the kind of thing that made me want to start this band… it’s why I chose to name this band Marilyn Manson.” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 46 | Grogan, S. | NME | 14/06/1999 | Interview | “The thing that happened in Columbine has been happening since the beginning of time… it inspired me more and I think it’s gonna show on my next album.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Youth Panic |

| 47 | Taylor, S. | The Observer | 04/07/1999 | Feature | “A few weeks later, it became clear… not only were they not fans, but they positively hated Marilyn Manson.” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 49 | Murray, C. | Seven Magazine | 08/ 1999 | Interview | “The only thing that scares me is to lose the power and strength of my own individuality.” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 52 | Marilyn Manson | Bomb City Foundation | 2000 | Transcript | “I don’t even think seeing violence is Brand New, that’s not the problem. What I think is the more serious problem is that seeing violence as a solution to solve a problem is what is sending a bad message to kids growing up.” | Gun Politics; Moral Decline |

| 55 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 11/11/2000 | Album / Lyrics | “So when we are bad we’re going to scar your minds.” | Youth Panic |

| 56 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 12/11/2000 | Album / Lyrics | “I’m a teen distortion, survived abortion, a rebel from the waist down.” | Youth Panic |

| 57 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 13/11/2000 | Album / Lyrics | “Some children died the other day… you should have seen the ratings that day.” | Youth Panic; Satanism & Scapegoating |

| 58 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 14/11/2000 | Album / Lyrics | “If they kill you on their TV, you’re a martyr and a lamb of god.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Celebrity Deviance |

| 59 | Unknown | ABC News | 15/11/2000 | News article | “”I think that art of all sort, whether it’s music or comedy or literature or even journalism, everything flourishes under conservative rule, because it gives people something to rail against,” says Manson.” | Gun Politics; Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 60 | Simunek, C | High Times | 02/ 2001 | Interview | “For anyone who has a Marilyn Manson CD, they have a Bible in their house and they also have the news to watch.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Celebrity Deviance |

| 63 | Guarino, M. | Chicago Daily Herald | 08/06/2001 | Feature | “I saw it happening and they hadn’t yet mentioned me but I thought, ‘Oh, I bet I get blamed for this.’” | Satanism & Scapegoating; Media Blame |

| 64 | Goldyn, A.R. | Omaha Reader | 19/06/2001 | Interview | “I think that when you’re trying to find out why kids act up and do violent things, it’s most likely because no one’s listening and they have something they want to say.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Youth Panic |

| 65 | Moore, M. | MansonWiki | 15/11/2002 | Interview | “I wouldn’t say a single word to them. I would listen to what they have to say. And that’s what no one did.” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 66 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 13/05/2003 | Album / Lyrics | “Babble babble, bitch bitch… sex sex sex and don’t forget the violence.” | Moral Decline |

| 67 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 14/05/2003 | Album / Lyrics | “You came to see the mobscene… It’s better than a sex scene.” | Celebrity Deviance |

| 68 | Marilyn Manson | Nothing/Interscope | 15/05/2003 | Album / Lyrics | “This isn’t music, and we’re not a band, we’re five middle fingers on a motherfucking hand!” | Media Blame & Hysteria |

| 70 | Brannigan, P. | Kerrang! | 20/04/2020 | Feature | “The media has unfairly scapegoated the music industry and so-called goth kids and has speculated – with no basis in truth – that artists like myself are in some way to blame.” | Media Blame & Hysteria; Satanism & Scapegoating |

Note. Adapted from Source Log (Appendix, Table A3)

4.4.1 Thematic Discourse Analysis

Three themes dominate defensive sources:

- Media Blame & Hysteria. Defensive sources frequently redirected blame away from Manson and towards systemic cultural issues. In his Rolling Stone op-ed (1999; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 44), Manson argued:

“We’re the people who sit back and tolerate children owning guns, and we’re the ones who tune in and watch the up-to-the-minute details of what they do with them.”

Here, Manson explicitly reframed responsibility as collective rather than individual. Instead of accepting the role of folk devil, he highlighted wider social failures, from permissive gun culture to the voyeurism of 24-hour news, as the conditions enabling Columbine. The defensive framing both contested media scapegoating and illustrated his ability to counter hysteria with systemic critique.

- Gun Politics. Defensive framings also redirected attention toward America’s relationship with firearms. Bowling for Columbine (Moore, 2002; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 65) highlighted gun availability as the structural context for the tragedy, reframing panic as systemic rather than cultural. In the same film, Manson himself critiqued the political deflection of responsibility, observing:

“The two by-products of that whole tragedy were, uh… violence in entertainment and gun control… The president was shooting bombs overseas, yet I’m a bad guy because I sing some rock’n’roll songs. And who’s a bigger influence, the president or Marilyn Manson? I’d like to think me, but I’m gonna go with the president.”

In this interview, Manson exposed the hypocrisy of previous political scapegoating: while structural violence was normalised through foreign policy and domestic gun culture, entertainment figures became convenient villains. By contrasting his role as a rock musician with that of the U.S. President, Manson underscored the absurdity of attributing causality to art rather than politics. This defensive framing reveals how scapegoating obscured systemic failures, further demonstrating his use of counter-branding to challenge dominant narratives.

- Celebrity Deviance (Reclaimed). Defensive framings also show how Manson embraced his role as a cultural provocateur, converting accusations of corruption into a brand strategy. Lyrics from This Is the New Shit (Marilyn Manson, 2003; Appendix, Table A3, Source Log ID 66) exemplify this defiant posture:

“Babble babble bitch bitch

Rebel rebel party party

Sex sex sex and don’t forget the violence

Blah blah blah got your lovey-dovey sad-and-lonely

Stick your stupid slogan in

Everybody sing

Are you motherfuckers ready

For the new shit?”

Here, Manson parodies the empty repetition of consumer slogans and media hysteria, deliberately aligning himself with deviance and excess. Rather than rejecting claims of obscenity and violence, he exaggerates them into performance, transforming scandal into spectacle. This is consistent with McRobbie and Thornton’s (1995) concept of counter-framing, where deviance is not denied but strategically re-appropriated. In this way, hostile framings of celebrity deviance were reclaimed as subcultural authenticity, reinforcing Manson’s brand as both a folk devil and a self-conscious satirist of panic culture.

4.4.2 Semiotic Discourse Analysis

Defensive framings reappropriated imagery to contest scapegoating. The 1997 “Unsafe” photograph (Figure 16; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 6) foregrounded Manson’s own branding. Denotatively declaring risk, the slogan was connotatively reworked as counter-identity. By exaggerating his role as a cultural menace, Manson transformed accusations into subcultural capital, reclaiming Celebrity Deviance as a badge of authenticity. This strategy prefigured his post-Columbine resistance to scapegoating.

Figure 16

“Unsafe” photograph, 1999 (Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 6).

Note. Retrieved from https://www.rollingstone.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/rs-179668-85243215.jpg?w=1581&h=1054&crop=1

The Disney ears with fanged mouth photograph (Figure 17; Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 20) similarly reworked panic discourses. Denotatively combining Mickey Mouse, a childlike corporate icon, with a sinister open mouth, the hybrid mocked consumer innocence while satirising media appetite. The logo on the cap, though blurred in artistic choice, is identifiable as the Death’s Head insignia worn by the Nazi SS (Figure 18). This appropriation compounded the unsettling hybridity: the childlike “Disney” allusion, the monstrous maw, and the invocation of fascist violence. Connotatively, the image redirected panic back onto commercial and journalistic systems, aligning with Media Blame & Hysteria by highlighting how rage itself was commodified.

Figure 17/18

Left: Disney Ears with fanged mouth photograph (Appendix, Table A4, Image Log ID 20). Right: Cap, Service Dress (General) Waffen-SS.

Note. Figure 17 retrieved from https://manson.wiki/File:Entartete_Kunst.jpg

Note. Figure 18 retrieved from https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30091051